Campus Protests Against Metal Detectors Build Steam

February 22, 2021

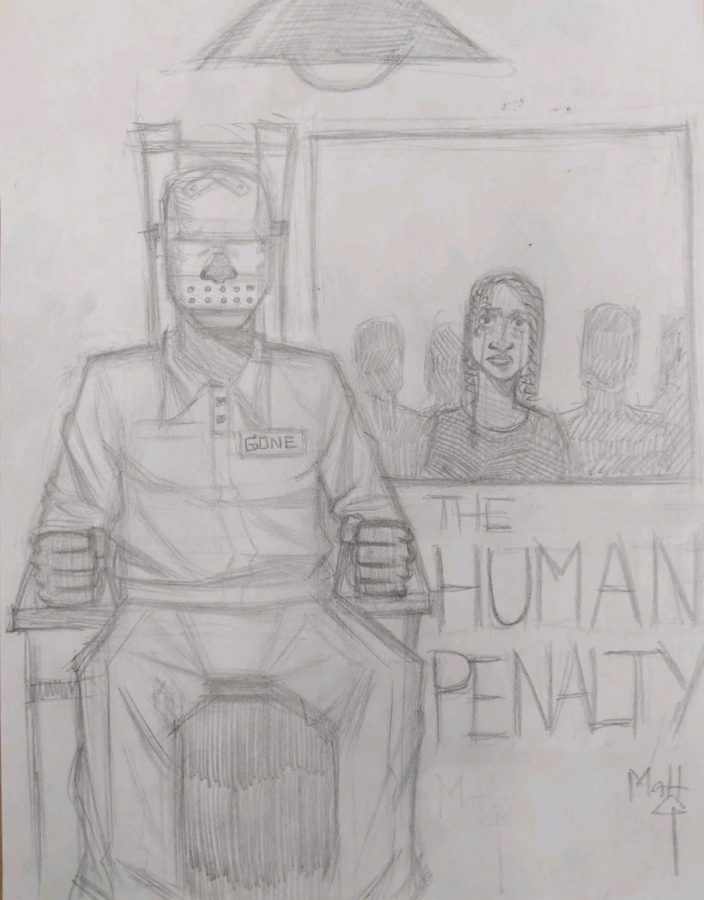

According to a report by The Brooklyn Eagle, on March 26th 2015, Noah Phillpotts, a student at the John Jay campus, was forced down and handcuffed by a safety officer by the metal detectors at the building’s entrance. He had entered the school and was stopped by a safety agent because a metal pin holding his glasses together set off the metal detectors. The safety officer allegedly elbowed Phillpotts in the face and took his glasses, perhaps believing the pin could be used as a weapon. It has been five years since this event, yet a coalition of John Jay parents and teachers called the John Jay Campus Metal Detector Removal Working Group (JJCMDRWG) are advocating to remove metal detectors from the campus. This effort is just a piece of their stated mission to eradicate practices in schools that divide students by race, in order to make the John Jay campus a place where all students feel part of a safe and inclusive community.

In order to get rid of the metal detectors on the campus, the principals of Millennium, Park Slope Collegiate, John Jay School for Law and Cyberarts Studio Academy have to agree to the change in policy. But only two out of the four, PSC and Millennium, have. Amanda Zinoman, a parent of a sixth grader at Park Slope Collegiate, recalls that at a community forum, the principals who didn’t comply, were asked how they felt. “Each of them basically punted, and said, ‘Oh, well, we have to hear from our community, and they [the principals] are not willing to take a stance on it.”

The movement against the metal detectors initiated with the PTA at Park Slope Collegiate. PSC was founded on anti-racist ideologies. Per their website: “The PSC experience is built upon the vision of a truly integrated school—racially, ethnically, economically, and academically—that leads toward developing a just and equal society.” The school’s leaders agree that the metal detectors imply to students that the campus is unsafe. Zinoman explains that the protocol of entering through metal detectors is “treating kids like there’s going to be a problem before you even start.” She and other PSC PTA members argue that it is degrading for students to start their day this way.

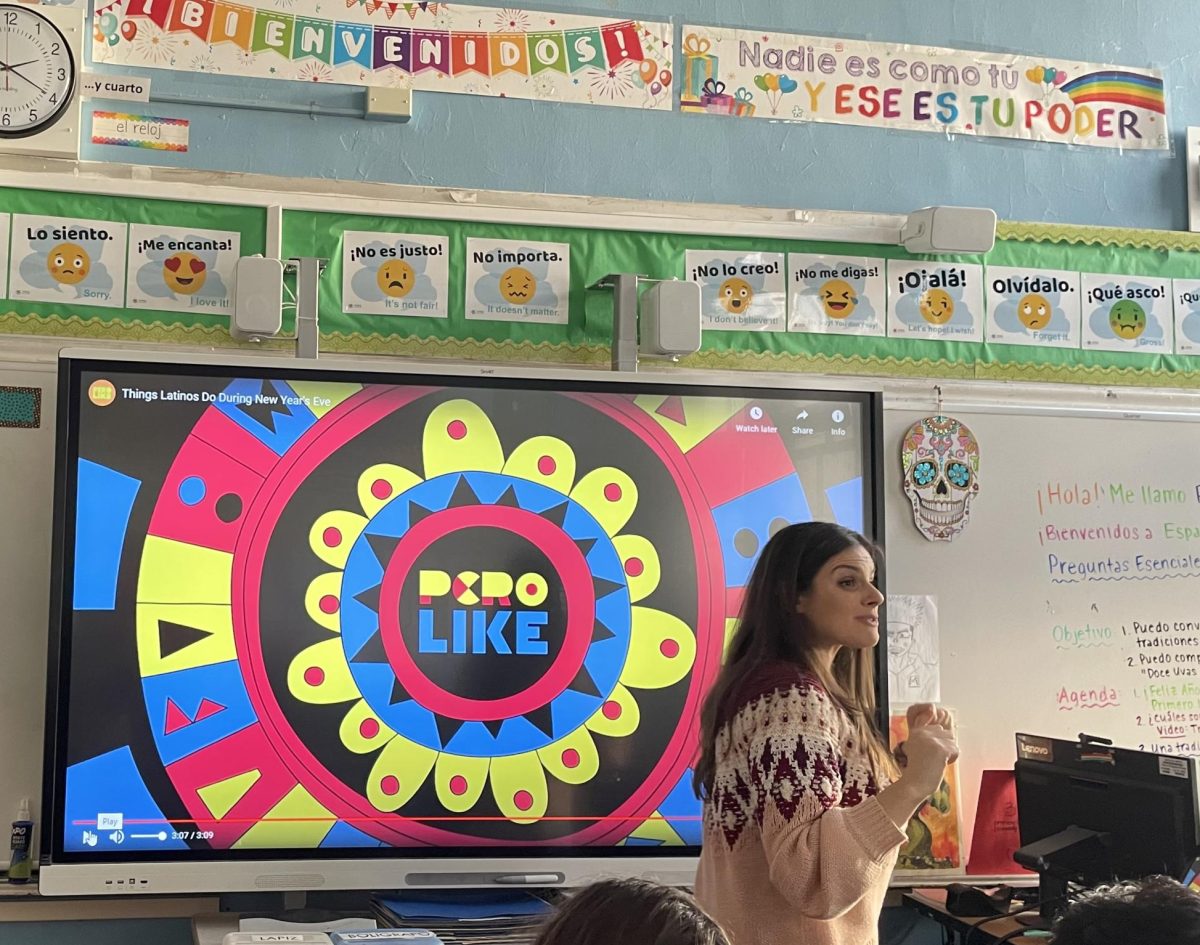

“If you’re from a community that doesn’t have a negative relationship with police, then maybe metal detectors aren’t that big of a deal for you,” MBHS Art teacher Ms. Davidson observes, “But if you’re from a community where the police represent, [the idea that] ‘there’s something wrong with us, that they need to patrol us’ then it’s reinforcing that, and it could be subconscious.” Ms. Davidson has been working for years with Campus Council, a campus-wide student group, who are working to confront tensions between schools and discuss the ways that segregation and systemic racism manifest in their day to day lives on campus.

The first metal detectors were brought into NYC schools in 1988 after a shooting at Thomas Jefferson High School. Soon after, numerous schools around the city installed the devices. The crime rate in New York City has dropped dramatically since the number of murders in the city peaked in 1990, according to a 2017 report by NPR. While metal detectors were put in place to prevent incidents such as the one at Thomas Jefferson High School, crime in schools have hit record lows in recent years, a trend in part attributed to the adoption of restorative justice practices, which the New York Times Magazine covered in a 2016 feature. The PSC PTA advocates removing metal detectors because they send a message that they target students of color.

Metal detectors may just be seen as simply a typical safety precaution, however not all schools have them. Many elite schools like Brooklyn Tech, Beacon and Stuyvestant do not have metal detectors, even though they have hundreds of students. Ms. Davidson stressed that “there’s a stereotype that kids that come from certain neighborhoods are just going to start violence with people they do not know or have no history or issue with. The perceptions within and across schools on our campus that they need to be protected from each other most is not based on any actual experience they’ve had.” The Metal Removal Group is trying to counter such biases, and prove that having metal detectors in schools can be dehumanizing. School shootings shouldn’t be dismissed as an unimportant issue. Ms. Davidson states, “[But] if the city was really going to use metal detectors to protect against school shootings, then all the schools would have them.” According to WNYC’s report “Metal Detectors in New York City High Schools,” only 33 percent of all New York City high school students go through metal detectors. However, 48 percent of Black students and 38 percent of Hispanic students pass through them daily.

Members of the JJCMDRWG insist that they are opposed to the metal detectors more than they are advocating the removal of safety officers. Ms. Davidson believes that “the safety agents are well intentioned people. Some of them are really wonderful, but I think they’ve also internalized that Millennium is the ‘better’ school with the ‘better’ kids.” Millennium is regarded as the most selective school in the building, with rigorous admission requirements that are seen as, in the eyes of some, exclusionary. Teens Take Charge, an organization of teenagers across New York City fighting for equity in the city’s schools, recently sued the DOE claiming that the school application process is racist and continues to segregate schools. The lawsuit bases its case on data showing that the ratio between the number of applicants and the number of students accepted differs greatly according to race; Teens Take Charge argues that a racist screening system, rather than ability, determines the composition of students at high schools across the city.

In interviews with the Millennium Phoenix, some parents, teachers and students at the John Jay campus have expressed frustration that the schools in our building feel disconnected from each other. Davidson notes that “people are looking for restorative justice, ways to create safety and community. And you’re less likely to hurt your community if you feel connected to it.” She adds that, “If we don’t talk to each other, it just perpetuates stereotypes and tension.”

At a community forum organized by the JJCMDRWG on January 7th, students, parents and teachers from all four campus schools came together to express viewpoints on school safety and equity, but also for the airing of sometimes hidden tensions among campus community. Students and a parent from CASA (formerly the School of Journalism) expressed frustration at being left out of the planning of protests and conversations around these issues, though the Campus Council had previously tried to recruit students from CASA and the School of Law to participate in such efforts. Davidson, who attended, noted that students, parents and faculty from all the schools “shared their reflections, ideas and hopes, and the students who were particularly frustrated and vocal at the forum shared a sense of gratitude for being heard and for the progress that came out of that difficult, and necessary, initial conversation.”

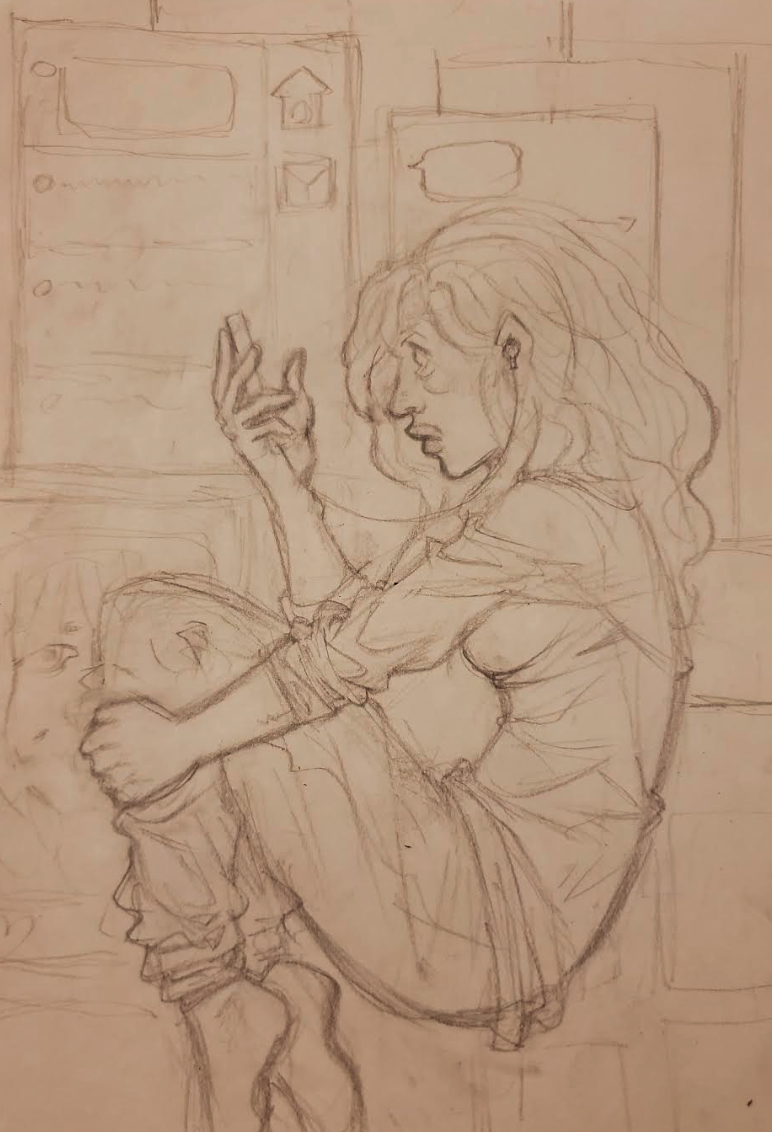

At the forum, students of color from several of the schools on the campus reported feeling targeted for bringing what they see as everyday objects onto campus. Brys Peralta Grant, a 12th grader at Millennium, shared one such experience. He recounted an incident where he brought his metal hair pick to school. “I wanted to show it to my friends,” Grant said. “I took it to school and we had to go through the scanners, and I figured it’s just a pick, so I’ll be fine.” The hair pick was confiscated by the safety agents. “Because it was in the first month of school and I didn’t really know the school officers…I was very put off by this whole system of ‘Oh, this is something metal so it equals dangerous.” Another time, he was stopped by safety agents when he was returning a glue gun and tripod to the school during Regents Week. Grant felt like the safety agents were assuming that since “[the glue gun] is metal and I have it [that] I’m intending to go into the school–which I love very dearly–and burn people that aren’t even there.” Grant noted that “the metal detectors have this added effect of…finding the problem with each student.”

Mariah Morgan, a 10th grader from Park Slope Collegiate, also spoke at the forum. She reported that her hair picks had been taken from her as well as her bobby pins. Morgan said, “The first time they [the safety agent] took it [her hair pick], he told me it was dangerous and it was a weapon…[S]traight to my face, he said ‘You can stab someone or you can go hurt someone with the pick.’” Morgan also added that, “When I was asked to think about all the bad situations I’ve had with security and metal detectors–you almost become desensitized to it. I feel like that’s why a lot of kids in my school, Black and white kids, they think this is the norm and they think this is okay, but it’s not.” She also noted that hairpicks were an essential part of her daily regimen. “As a Black woman, they are essential to my personal care. It may seem trivial…but it’s a tool for me… I don’t think it’s the same for white students.”

Belts, jewelry, hair pieces and shoes can all set off the metal detectors. During the winter, Morgan wears Timberlands, and after setting off the metal detectors and getting wanded every day for a week, she reported that the security guards told her to buy different shoes.

Throughout the meeting, students and parents shared their experiences and opinions but there were some disagreements between the students at CASA and the other schools, along with questions of if the metal detectors truly are the cause of the racist mistreatment of students or if the removal of the metal detectors will only bring more white students to the campus. Overall the forum was a good way to continue the discussion and bring together the schools and have a meaningful conversation.

Zinoman argues that “this is something very concrete that affects my son everyday.” Many parents of Black students or students of color see the metal detectors as yet another way their children experience racism. Zinoman says that “even if no one is getting physically hurt by the metal detectors, that doesn’t mean that they aren’t something that stands for treating kids like they are already guilty before they start their school day.”

Noah Phillpotts, the student who alleges that safety officers used excessive force against him in 2015, has since sued New York City schools for the incident. But members of the JJCMDRWG note that the fear of being punished can be a big weight for students of color to carry. Ms. Tannis, a Millennium teacher working with the group, notes that when someone like a safety agent occupies a position of power, “Basically [they’re]…assuming criminality and when you don’t comply, even if you’re not a criminal, I have the right to enact violence on you.”

Even though students are not currently attending school in person, Zinoman also makes the point that “because of COVID, [on in-person school days, the metal detectors] really make this 100 times worse, people have to wait in line.” Overall, JJCMDRWG members feel that the school would be a more safe and accepting community without metal detectors. “All the money that’s spent on them could be spent on school counselors, could be spent on outreach, social workers,” Zinoman adds.